If you grew up in the 80’s and 90’s—especially in the USA—you’re likely to have listened to your favorite music off the radio or from cassette tapes (before CDs started taking over), played on plastic “boom boxes” or on little headphones with colorful foam pads that would sit on your ears. Or maybe you’d hear this music coming from the car radio playing through little speakers in the car doors.

In any case, the audio reproduction options most of us had at our disposal in those days—almost regardless of the money available to invest—were nowhere near the performance and fidelity of the consumer electronics we have today. Even a set of modest Bluetooth headphones can blow the pants off what those old systems were proud of doing in the prior decades, even with all the shortcomings and pitfalls we know Bluetooth audio has of its own.

The point is: Improvements in consumer playback solutions affect improvements in music production techniques. As the consumer listening environment changes, the content providers need to support that change. As a consequence, the music we hear today does sound better than the music of the past. Not that the artists of the past were shit or didn’t know what they were doing (though there will always be some of those in any age), but that they were slaves to their own technology. They could only hear as well as their tech could let them…and they really only needed to make it good enough for the popular playback media of the time.

In order to prevent any jarring effect when our “new ears” hear this older music, we need to compensate for the change in styles that have occurred between then and now. We need to do this compensation to the music because our brains already have done this compensation on a subconscious level. We hear a modern recording by a modern band played on modern sound equipment and we think: “I know what it should sound like if the song __________________________________ by ______________________________ were to come on right after this one.” The current song has set various expectations for us in terms of overall loudness (which is determined by correct application of dynamics processing and choices over the aggressiveness of their application), stereo field and width (driven by the separate access and use of the stereo channels), and frequency profile…all of which leads a person to answer the question of “what is flat right now?” based on what they can currently hear.

If the modern song achieved their overall loudness, stereo width, and frequency profile using modern tools and playback equipment which didn’t exist at the time when _________________ made the song _______________, then those tools still need to be applied to make the song sound great on modern playback equipment.

I believe the above thesis also holds true for the SID music coming out of the Commodore 64. Therefore, we should apply many of the same tools and technologies used for modern music production on SID music so that SID music sounds great on modern playback equipment and can compete with modern recordings.

In the quest to achieve the best SID audio, there are three different levels, goals, or targets that one may try to hit along a path: Cleaning up the audio signal, modernizing the sound profile, and enhancing the sound beyond the original. The next sections will look at each in detail.

Cleaning up the Audio Signal

I don’t know who was sloppy first, but it seems some aspects of the Commodore 64 electrical design are so poor that the only possible reason for it is because they knew the audio and video signals “would never be played on anything better than a television set.” Indeed, that’s how everyone obtained video output from their computers and game consoles in those days—one video display had to be shared and perform multiple tasks in a household as they were not cheap to come by. So the design specs of the Commodore 64 are such that, on its best day with all its makeup, best heels, and a push-up bra, the video quality will never exceed NTSC or PAL video format and resolution. So there’s the whole issue of “how does one view the video from a Commodore 64 in the 21st Century?” a question whose answer took lots of research and product trial-and-error.

Then there’s the situation of the audio. As this was generally intended to be mixed into the RF signal with the video to be played out the TV after being tuned in on a “blank” TV station, the audio also didn’t need to be very clean. Even the cleanest of source audio would still come out of the TV’s speaker covered in muck back in those days. And while it was smart to start as clean as possible, the whole “diminishing returns” had to be considered and someone had to say “that’s good enough” and they went with it. As a result, even with her best foot forward, the SID chip is still going to sound a bit crusty and dirty. And it will have noise in it from the video signals and oscillators.

Once steps are taken to reduce those effects, you end up with some thing that actually resembles a proper analog synthesizer...like a “proper” synth of the type you’d use in the studio. The output quality is actually quite good when taken directly from the SID chip output (bypassing all the video pathways it would normally take on its way to the TV). There is an Audio Output pin on the round Video Output DIN connector on the back of the C=64—with the right cable, or via soldering a lead from the rear of the jack inside the C=64, you can get a signal from the SID that has had a very short trip from the output pin of the chip.

You can additionally try techniques of grounding or lifting the Ext Input pin on the SID chip. As virtually nothing for the C=64 makes use of the external audio input pin, it mainly serves no purpose. Unfortunately, its presence and ability to bypass the SID by default, means that it can pick up noise from the computer and feed it right to the SID’s output. By connecting the Ext Input pin to ground (sometimes through a coupling capacitor), this will often greatly reduce the volume of the noise being introduced from this source.

In two of my C=64C computers, I use the SidFX solution which, along with many other benefits, manages the silencing of the Ext Input pin as well as providing discrete audio outputs from each SID where the signals never touch the C=64 mainboard at all and just go straight to the output jacks on the rear of the computers.

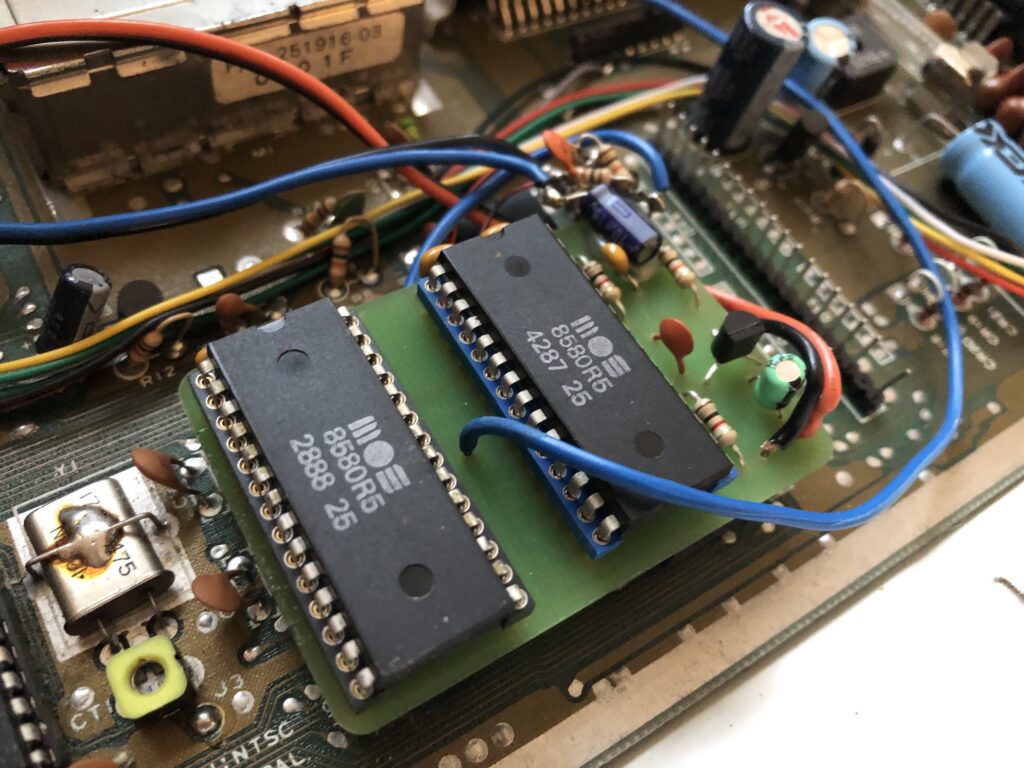

Prior to SidFX, I used the SID2SID solution which, along with the add-on audio amplifier, also provided discrete audio outputs for the two SIDs which bypassed the mainboard:

Clean audio recordings taken directly from “noise sanitized” SID chips is generally considered the 100% true way to capture and listen to SID music (the type of SID used for playback, be it the 6581 or 8580 variant, is usually noted as part of the recording).

Modernizing the Sound Profile

At this stage of improvement, the somewhat “flat” or even “nasal” sound profile of the SID output is re-shaped into a more modern curve which emphasizes bass, scoops out low mids, and adds a nice touch of “air” and “shimmer” in the highs. This is mostly done with equalizers.

Dynamics processing (leveling compressors and limiters) may also be used to continue development of a modern sound, especially if certain bass frequencies have been heavily boosted right before the processors. In addition to the “modern frequency curve” provided by the EQ, the dynamics processing now provides a “modern dynamic response” for the music.

With both of these techniques implemented well, the SID music can now hold its own reasonably well against modern electronic music tracks from CDs while still staying nearly 100% true to the “pure” spirit of SID music. In my case, I use the tc electronics Finalizer Plus and FireworX processors primarily for these purposes:

- Analog-to-Digital Conversion is done by the FireworX because it has a physical knob on the front panel for adjusting the input gain. Sure, the gain adjustment itself is likely in the digital domain (or at least being digitally-controlled)—I’m not expecting this knob to be an analog gain adjustment. I just appreciate the convenience of this knob because overall volume can vary drastically from one SID composition to another. This is especially the case when the composition makes heavy use of digital samples (the overall level is usually lower for these songs). I therefore tweak the input gain often. Physical knob good, even if it is a small one. And I trust the ADCs on this device aren’t crap by any means. The analog signal has to be captured via hoity-toity XLR jacks!

- Remove clock noise and other pitched elements using notch EQs on both the FireworX and Finalizer (since there are annoying limitations to how many instances of each you can run on each unit at a time). It’s usually possible to isolate these pitches precisely and set a very narrow bandwidth on the EQ and then notch it out without causing an obvious change in the overall tone of the SID music. While this sort of notching might create strange “reverse wind tunnel” effects, this effect is much reduced—or less noticeable—with SID music. I think this is because, even at its richest moments, SID music is still just the sum of three different waveforms. The ill effects of a notch EQ on such an audio source is minimal.

- Create the modern frequency profile using EQs with wide Q settings or, in the case of bass and treble, shelving EQs. Give the bass some oomph, add some “air” with a slight boost to highs, and scoop out a bit of low-mids, but not much.

- Gate the audio during silence using the Expanders on the Finalizer Plus. Even with maximal cleanup, a SID chip still outputs sound (such as VCA leakage) when it should be silent. The Expanders allow the audio to be taken down to virtually -inf dB when the signal gets below -60 dBFS. Music can therefore start from silence (and generally end gracefully in silence, too).

- Ensure maximum digital output level via the output limiter of the Finalizer Plus. Some soft clipping is employed at this stage, all with a target maximum output of about -0.3 dBFS.

Enhancing the Sound Beyond the Original

When producers work with synthesizers, they do start with the cleanest version of its sound they can get—when using a virtual instrument (like a VSTi), they get the direct digital output of that synthesizer, just like a hardware synth with a digital output (like an Access Virus TI). When using hardware synths that lack digital outputs, which is the vast majority of them, especially those with analog voice architecture, producers will usually plug these directly into the line inputs of an audio interface and then proceed to treat the synth like any other track (such as the parts made by a VSTi) using processing plug-ins, doing the final mix in the computer, etc. It’s that “using processing plug-ins” bit I want to focus on here.

Indeed, even with the “best sounding” synth, there will come a need to put it through some EQ or do some kind of post-processing to its audio signal. It’s not a matter of just calling up synths and pushing the faders up. Modern mixes are sculpted carefully to maximize audio frequencies and an objective “intensity”. If producers are using post-processing techniques on even the best synthesizers in the world, how is SID music going to compete with that?

The answer is to use the SID chip just as any other audio instrument and apply any or all of the same musical techniques and strategies towards it. For example, if a guitarist will double-track himself—that is, make two separate recordings of himself playing the same part which are then panned apart from each other during playback—to give a nice stereo sound and chorus effect to his sound, use that same technique with two SIDs playing the same music panned apart to give a nice stereo sound. Or play different parts to each SID to create more complex compositions with double the voices.

It turns out there are numerous solutions for installing a second SID chip into the Commodore 64 such that the second chip can play back exactly what the first chip is playing (by putting the second chip on the same exact address bus as the main chip) or such that it can be played independently (by putting it on one of a handful of different addresses, such as $D420 and $DE00). I originally had something called SID2SID installed in my Commodore 64C, but that has since been replaced by SidFX which currently holds two 8580R5 SID chips (the type native to that particular C=64C model). Of the many benefits of the SidFX, the one exploited here is the software-adjustable address assignment of the second SID. The latter greatly improves compatibility with both software and SID files that support some kind of second SID as there was no hard-and-fast standard ever developed and published for this by any important body, and also allows an easy “fallback mode” where the second SID just mirrors the first SID for dual-mono / pseudo-stereo output.

In addition to this hardware upgrade to enhance the possibilities of the SID, further signal processing techniques can be employed in an effort to bring SID music comfortably into the 21st century. In the case of the Commodore 64C discussed here, as well as the Amiga 1200 discussed elsewhere, a common processor I employ is the Zoom MS-70CDR:

This unassuming and affordable guitar stomp box is actually a near-perfect audio Swiss Army Knife which is being used for its “Exciter” module which is one of the stereo processors in the unit. Even with its parameters set to zero, the Exciter has a wonderful enhancement quality that I think pairs perfectly with the SID. Not only does it give the sound profile an even more modern vibe, but it does something to improve—or in this case, widen—the stereo image. This is important because, even with two SIDs panned apart, most SID music still images as mono at the dead-center of the stereo field. This is because the oscillators of the SID are digitally-controlled and, being precision digital instruments, their waveform cycles match precisely when they play. There are no phase differences between the two, only slight overall EQ and volume differences, so dual-mono SID music still basically sounds mono, the only difference being that any white noise-based sound will be in super-stereo as the white noise generators seem to be unsynched and therefore running independently on the two SIDs. The Exciter on the MS-70CDR can therefore help introduce a greater sense of stereo where one is generally lacking (and needed). It’s really the “secret sauce” of getting the great sound from my Commodore 64C.

SID Recordings

You can hear the results of the above audio enhancement when listening to any of the Commodore 64 or SID recordings posted on this site. For convenience, you can browse all recordings here: